For those unfamiliar with the art world, an artist’s statement is meant to provide a context for a series of work, or even a career. It’s like the plot of a A Place in the Sun (the film version of An American Tragedy), where the protagonist’s guilt is decided by what was in his heart, when his pregnant ex-girlfriend went into the lake. If you’re doing a painting for one reason, it’s a different painting than if the exact same image is created for a different reason. Unfortunately for me, I’ve never really bought into that. In fact, I’ve always felt that having to produce such statements were a necessary evil.

But I just realized what fun I could have with a piece I did called MODERN VENUS — A CONTEXT, if I appropriated images from the web, and pasted in pictures from the 25 thousands years of art I was talking about. The original layout looked pretty good, but then a WordPress update blew it apart and I haven’t gotten around to straightening it out. So here it is, kind of a mess, but with great illustrations by everyone from Michelangelo to Tom of Finland.

MODERN VENUS — A CONTEXT by Edward Weiss

The most persistent theme in the history of Western (and other) art is the iconic depiction of the human body — it’s beauty and sexuality.

In ancient civilizations, such icons frequently were representations of gods. The world’s oldest existing sculpture — the Venus of Willendorf  and perhaps its most famous — the Venus de Milo, are two examples.Looking back from the 21st century, it’s tempting to see the deification of such transparently human forms as simply artists’ justification

and perhaps its most famous — the Venus de Milo, are two examples.Looking back from the 21st century, it’s tempting to see the deification of such transparently human forms as simply artists’ justification s for a libidinous desires to portray naked babes and beefcake. But I think the preponderance of gods and goddesses among the icons is an expression of the fact that the human form can move us in ways that are not totally explicable. Deifying these bodies is a way of grappling with this mystery.

s for a libidinous desires to portray naked babes and beefcake. But I think the preponderance of gods and goddesses among the icons is an expression of the fact that the human form can move us in ways that are not totally explicable. Deifying these bodies is a way of grappling with this mystery.

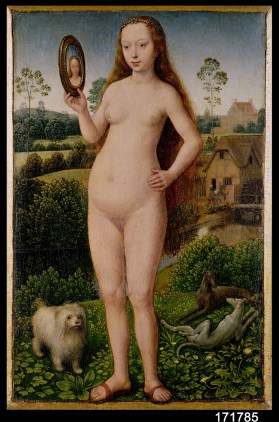

In the Middle Ages, (which followed the classical period), the rise of monotheism in the form of a patriarchal God, combined with the repressive spirit of the times, to limit such grappling. Though subjects like vanity did provide a vehicle for depicting a naked woman staring at a mirror, the occasional nude from this period is as likely to evoke a plucked chicken, as an object of worship. With the Renaissance however, a spirit of rapture returned to depictions of the human body. Roman Gods once again flourished as vehicles for glorification of the nude form. And with increasing frequency, mere mortals were also depicted with iconic beauty and sexuality. Though typically these mortals also had some sort of religious or mythological context, like Michelangelo’s David, or Titian’s Bacchanal of The Andrians.

With the Renaissance however, a spirit of rapture returned to depictions of the human body. Roman Gods once again flourished as vehicles for glorification of the nude form. And with increasing frequency, mere mortals were also depicted with iconic beauty and sexuality. Though typically these mortals also had some sort of religious or mythological context, like Michelangelo’s David, or Titian’s Bacchanal of The Andrians.

By the late nineteenth-century, the ever-popular themes of religion and myth had diverged from glorification of the body. So much so that leading practitioners of these genres like the Pre-Raphaelites, Gustave Moreau, Puvis de Chavannes, etc., seemed to revel in painting ascetic (though lovely) figures.

By the late nineteenth-century, the ever-popular themes of religion and myth had diverged from glorification of the body. So much so that leading practitioners of these genres like the Pre-Raphaelites, Gustave Moreau, Puvis de Chavannes, etc., seemed to revel in painting ascetic (though lovely) figures.

This context was so established that realist painters like Courbet and Manet invoked outrage for paintings of robust contemporary women, (sometimes also with mythological titles) who might in current vernacular, be described as “hotties.” Ironically however, their paintings now seem to reflect the spirit of ancient precedents better than the more delicate work of the 19th century allegorical kitschmeisters they were rebelling against.

Despite a continuing push towards abstraction, Modernists who followed in the wake of Manet – Modigliani,  Picasso, Matisse (the Odalisque series) and numerous others – continued to explore the iconography of the body until the ascendancy of the abstract expressionism of the New York School.

Picasso, Matisse (the Odalisque series) and numerous others – continued to explore the iconography of the body until the ascendancy of the abstract expressionism of the New York School.

Of this group, only Willem de Kooning would attempt to reconcile concrete body iconography with near total abstraction in his remarkable Woman, and Marilyn, paintings.

Paradoxically, at the same time, representational artists like Freud and Pearlstein seemed bent on demystifying the naked body by portraying it as mundane or even repulsive.

Not surprisingly, this changed when Pop Art took center stage. Its focus on the iconography of popular art included much attention to the body. Some artists, like Tom Wesselman and Mel Ramos, even made this their primary or exclusive focus.

But they were hard put to surpass their source material, the classic pin-up art of the mid-century. The technically adept artists working in this genre (Gil Elvgren, Joyce Ballantyne and Peter Driben, etc.) often-depicted scenes that seemed to have sprung straight from a semiotician’s fever dream.]

Perhaps the most mind-blowing example of this is the unforgettable ” “panties-falling-down” series by Art Frahm, and Jay Scott Pike that depicted various scenes of a fully clothed young woman who (while performing a mundane task, like carrying home the  groceries) suddenly experiences a loss of elasticity that sends her underwear to her ankles. Thus setting off a reaction among passers-by that is the seismic equivalent of the San Francisco Earthquake of 1906.

groceries) suddenly experiences a loss of elasticity that sends her underwear to her ankles. Thus setting off a reaction among passers-by that is the seismic equivalent of the San Francisco Earthquake of 1906.

Though sexually iconic depictions have continued unfettered in popular culture to this day, their presence in the gallery world has had a more torturous path. Undoubtedly, the inundation and increasing banality of body imagery towards the end of the 20th century (Baywatch, Pussycat Dolls etc.) in pop culture has had a negative effect, as have questions about the validity of such imagery, specifically the notion that objectification is violence against women.

The erroneousness of this widely accepted concept is revealed in the fact that its original proponents, Dworkin and MacKinnon included gay male eroticism in their thesis. But the jawdropping unreality of a concept that would suggest that depictions of two guys boinking (or artwork that objectifies male bodies like Tom of Finland or Michelangelo) is somehow violence

or Michelangelo) is somehow violence

against women – has not limited its influence.

The 25,000-year history of body iconography in art is also a deterrent to new work along these line, as it flys in the face of the requisite conceptual newness that is the gallery artist’s stock in trade.

And indeed, one does need a touch of hubris to mine this well-worn vein in search of some  remaining gold. But on the other hand, it’s an interesting place to dig around in. When I started the Modern Venus series, my goal was to combine a modernist abstract compositional sense with the fervent representationalism of classic pin-up art. But I wanted to make a break from the pin-up and other iconic art in one sense. Part of this tradition has idealized the figure by rearranging it in some sense – exaggerating or streamlining certain proportions. I deliberately haven’t done this because I wanted to capture the way the eye seeks out the superhuman in the human. Rather than idealize the body, I wanted to reflect the powerful mystique that lurks in the commonplace.

remaining gold. But on the other hand, it’s an interesting place to dig around in. When I started the Modern Venus series, my goal was to combine a modernist abstract compositional sense with the fervent representationalism of classic pin-up art. But I wanted to make a break from the pin-up and other iconic art in one sense. Part of this tradition has idealized the figure by rearranging it in some sense – exaggerating or streamlining certain proportions. I deliberately haven’t done this because I wanted to capture the way the eye seeks out the superhuman in the human. Rather than idealize the body, I wanted to reflect the powerful mystique that lurks in the commonplace.

So I set some ground rules for myself. No intentional anatomical distortion whatsoever. No depictions of surgical enhancements (i.e. silicone). And no violating the laws of physical reality, even with the invented stuff – no blue-skinned people or impossible perspectives, for instance.

I also tried to avoid any imagery that would directly indicate some kind of situation taking place outside of the given one – that there is a posed figure in the painting.

Everything else was fair game. I’ve added clothing to figures that was not worn by the original models; and invented furniture for compositional purposes. Colors have nothing to do with the original sources and rendering is (I hope) heightened. My goal was not realism, but that element of unreality that is available to the naked eye.

Modern Venus #14, by Edward Weiss, Gouache and Acrylic 22″ X 30,” circa 2002

______________________________________________________________________________________________